Art

The influences of Pop-Art on contemporary Persian Artists

How Pop-Art has influenced contemporary Persian Artists: Hushidar Mortezaie, Amir H. Fallah, Farbod M. Mehr, Rabee Baghshani

By Lizzy Vartanian Collier

Pop Art originated in Britain and the United States in the mid 1950s. Despite being half a century old, its signature references to advertising, mundane objects and popular culture continue to inspire artists’ young and old across the globe, notably including many young Iranian artists. While this may be surprising, contemporary artists of Persian descent, both in diaspora and in Iran, are channeling Pop Art’s spirit in their work.

Pre-revolution, Iran had strong interactions with the West with Queen Farah Diba Pahlavi filling Iran’s first contemporary art museum with works by Andy Warhol and David Hockney as well as modern and contemporary artists from Iran. Warhol even created her portrait, complete with big hair and bright colours.

Raised in the US in the late 70s and early 80s, Hushidar Mortezaie witnessed Andy Warhol move from artist to celebrity first-hand: ‘There is a worship of beauty in his work, yet it has a critique, where he rips the piss out of capitalism, fame, advertising, politics and beauty…that is what Pop Art is about.’ Mortezaie’s work is full of Iranian women in colourful clothes, which often combine Eastern and Western influences. Speaking to Pop Art’s intrigue into the world of capitalism and consumerism, Mortezaie has been heavily involved in fashion throughout his career, working with Patricia Field and Michael Sears.

In his new venture Silk Road Super, an online ‘bazaar’ of ready-to-wear works of art, he includes the batman logo with Farsi script written across the centre, while printing the faces of Qajar women on polyester tote bags. ‘I made things with my voice and a distinctive language that also appealed to a modern generation of Iranians living abroad, especially in the USA’, says Mortezaie of his designs. When asked about the interesting cross-over between Iran and the US, he adds: ‘There is a bridge of commonality between the West and the East…we do see Orientalism on an all time high in the West…in the past the Persian satellite networks brought MTV and Britney and fashion shows to a hungry young Iranian audience, now with social media Tehran is about shopping, logo mania, fast food.’ It is not surprising then, that many young Iranian artists use these references across their work.

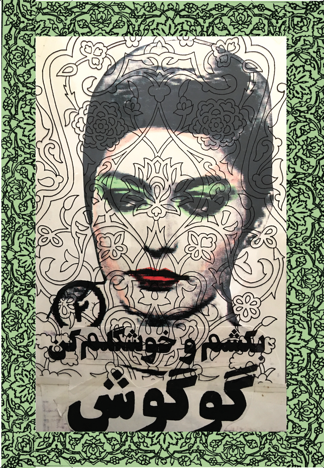

Farbod M. Mehr, who is based in Britain, mixes traditional Persian iconography such as Qajar figures and portraits of the royal family with technology and references to contemporary youth culture. ‘My work has some traces from Qajar to the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, but practically, it is influenced by Western schools and visual experiencing of Iranian versions of pop culture. This mutual cultural relationship is fascinating for me, and I try to focus on this border that Iranian and other cultures face encountering with each other.’

Farbod M. Mehr, who is based in Britain, mixes traditional Persian iconography such as Qajar figures and portraits of the royal family with technology and references to contemporary youth culture. ‘My work has some traces from Qajar to the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, but practically, it is influenced by Western schools and visual experiencing of Iranian versions of pop culture. This mutual cultural relationship is fascinating for me, and I try to focus on this border that Iranian and other cultures face encountering with each other.’

In It’s for my art, 2016, a man holds the hand of his female lover, whose head is tipped back in delight. He appears to be whispering sweet nothings to his darling. Both figures replicate traditional drawings in style however, a piece of the 21st century is inserted in the form of a blue text message like those received via i-message on an iPhone reading: ‘Wanna come over and destroy each other emotionally? It’s for my art.’

Mehr’s addition of the instant message to the work brings it back from history into the age of technology, where sexual and romantic communication have been transported from hushed secrets to those sent across a digital screen.

![]() While it is often believed that references to the West had been completely eradicated during Iran’s Islamic Revolution, Mehr explains that this was not the case: ‘Pop Art was one of the most important assets to convince people to follow the movement. From the fairy words of the leader to graffiti slogans, murals, posters and banners – words and images unified much of the nation.

While it is often believed that references to the West had been completely eradicated during Iran’s Islamic Revolution, Mehr explains that this was not the case: ‘Pop Art was one of the most important assets to convince people to follow the movement. From the fairy words of the leader to graffiti slogans, murals, posters and banners – words and images unified much of the nation.

At that time the popular beliefs and rituals disseminated a lot on such objects as stamps, textbooks, banknotes and chewing-gum wrappers, stringing people into a revolutionary trance through all aspects of daily life.’ It then follows that Pop Art has influenced not only Persian artists living in the West, but also those based in Iran.

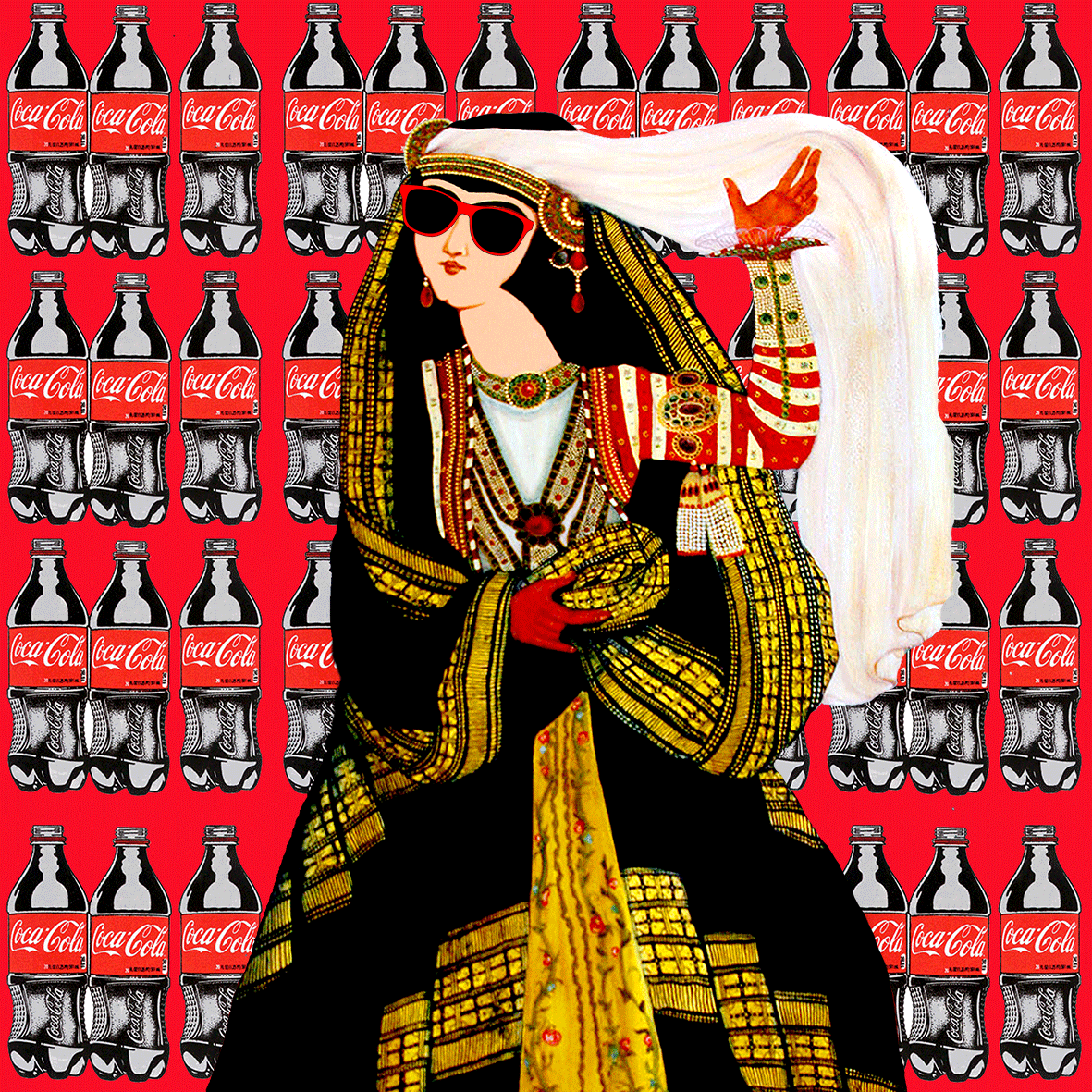

Living in Mashhad, Iran, Rabee Baghshani’s most striking images depict Qajar figures posing playfully in front of Western brands banned in Iran. Baghshani explains: ‘By using the Qajari figures in a Western context I want to show a satirical critique in my artworks.’ In one digital rendition, a woman gestures playfully in traditional costume with the modern addition of red sunglasses. She stands before a background of tiled Coca Cola bottles, whilst in Proliferation/McDonalds, 2016, a male figure is displayed in ceremonial dress in front of the golden arches of McDonald’s complete with the trademark slogan ‘i’m lovin’ it’ printed repeatedly across the image. ‘The brands used in my work are familiar in my country…using Pop Art, they [Iranian artists] are able to make a public critique of their community.’

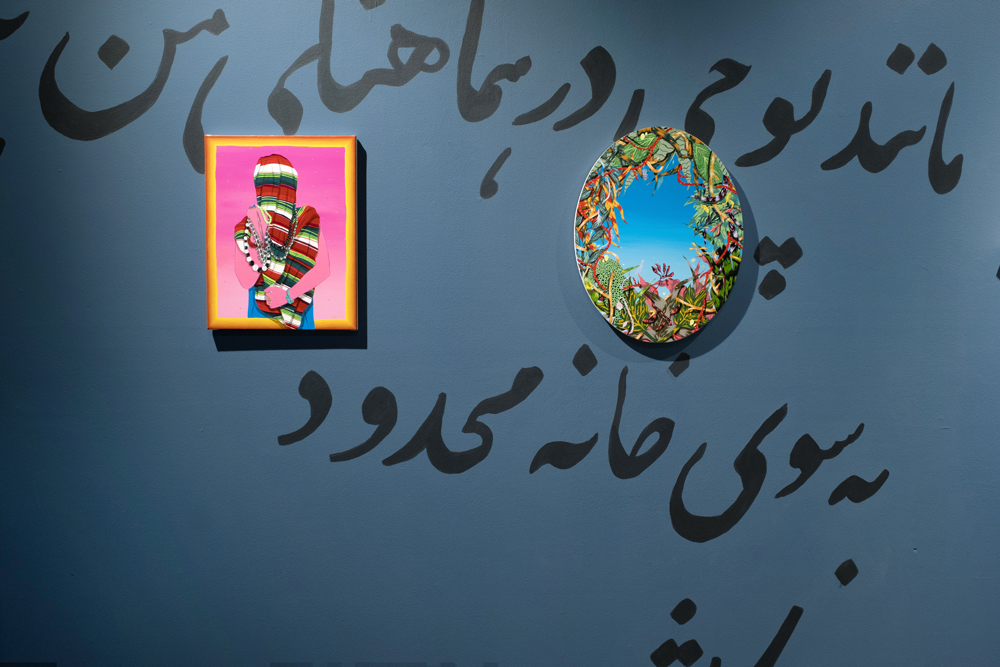

American-Iranian Amir H. Fallah does not explicitly reference Pop Art, though he does take samples from multiple art movements, both Eastern and Western: ‘I freely borrow from multiple eras in art history within the same painting.’ In his recent series Almost Home, Fallah paints a series of portraits of Iranian-American immigrants who have not returned to their homeland since departure. The exhibition took place in Dubai, closer to Iran than the US, but not quite there. The images include floral Persian ornamentation and reflect on the idea of belonging outside of one’s country of origin.

In Happiest Place on Earth, 2017, American influence blends in with Iranian symbols where a veiled figure appears in the centre of a circular canvas, clutching a Mickey Mouse toy.

Whether Mortezaie, Mehr, Baghshani and Fallah have been inspired by Pop or not, it cannot be denied that all of their work references the increasingly technological world that they have grown up in.

‘Given the virtual world today and with the disappearance of the geographical boundaries, the realization of culture, customs, etcetera is not a problem’, says Baghshani. ‘Iran is beginning to have a dialogue and do business with more nations in the West’, adds Mortezaie, ‘art always follows the times.’ We couldn’t agree more.

0 comments