Art

Muheb Esmat | Kabul Undiscovered

Muheb Esmat is an artist/curator born and raised in Kabul, Afghanistan. He currently works as a curatorial specialist at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. His interest consists in looking further to explore the roots of modernism in the Middle East. He talked to JDEED about two of his projects, 08.25.17 and a documentation of Kabul’s graffitis but also about the misconceptions people hold towards Afghanistan.

Muheb, please tell us a bit a bit about yourself and how you first started as an artist?

I am a product of a pre and post-2001 Kabul, where I grew up in two opposite states of a society. First a country in utter isolation and emptiness under the Taliban, then an open door to the world, where an influx of people and cultures were welcomed. Even from a young age, my family insisted on me pursuing calligraphy and drawing classes outside of school. But it has only been in the past couple of years while pursuing my college education in the US that art has become my preferred means of expression. I have struggled with self-expression, especially through words, as I often find language to be reductive in conveying our experiences. On the other hand, art and abstraction have given me the chance to reflect upon the past and present in ways that words and language usually can’t.

Would you say that there is an artistic community in Afghanistan? How is your origin country inspiring your work?

There has always been a community of artists in Afghanistan. It’s just that their lives and work have been either lost or overshadowed by the bigger game of life and death that the country has been grappling with for decades. At the moment there are some unbelievably talented artists working in the country or in diaspora. As for my own work, although it is usually abstract and geometric with a simple decorative appeal to it at first sight, at its core my work is autobiographical. It’s deeply influenced by my own past, which is subsequently a product of what has been going on in the country. In a more direct sense, I have sought inspiration from local traditions, specifically tribal designs or this past summer, I spent hours walking around Kabul looking for that little trigger to an inspiration.

What are the biggest misconceptions people have of Afghanistan and in this case, of its artistic scene?

I will have to say people only associate traditional forms and styles of of art, such as miniature, wood-working, and carpets with Afghanistan. They often are surprised by the idea of a modern and contemporary art scene. But just like everywhere else, artists in the country were fascinated with modern life, and more recently it has witnessed the rise of a contemporary art scene.

Explain to us the initial idea behind your project 08.25.17 and how you thought about this series? How do you believe that art can help shed light on geopolitical issues and in this very case, matters of terrorism?

It all started with an image on New York times of a pile of shoes left behind after an attack in a local mosque on August 25th. It left me speechless in thinking how hundreds of lives were changed for the worse after that single attack. In recent years Shia’s in Afghanistan and their congregation centers, like mosques, have often been targeted by the Islamic State and other militants. These mosques are the places where often innocent souls, young and old gather in search of redemption in the eyes of God and a short sanctuary from the worldly chaos around them. But it’s more than heartbreaking to see that often these souls don’t make it out because of the barbarity of a group that lacks any human values. Even the lucky ones that do make it out safe, leave behind their friends, family, hope, blood, tears, and shoes. With war, violence, and loss being a routine part of the life trajectory for decades, people often move past such atrocities in just a matter of hours or days. Which is not only an example of their strength but also speaks to the lack of options in living a normal and peaceful life. This project was an attempt to document some of the shoes left behind as a memorial but also evidence to the atrocities suffered by the souls that once walked in them. With the help of two kind souls, Jim Huylebroek and Johanna-Maria Fritz, I was able to put together 08.25.17. It is meant to offer a glimpse into these frequent events through the unusual voice of the shoes, often dumped and forgotten after the event, just like the beautiful souls lost. I believe art has a duty to mark and speak about the present, past and future. In this case visuals can convey a far greater message in not only highlighting geopolitical issues but also documenting them for future understanding and studies.

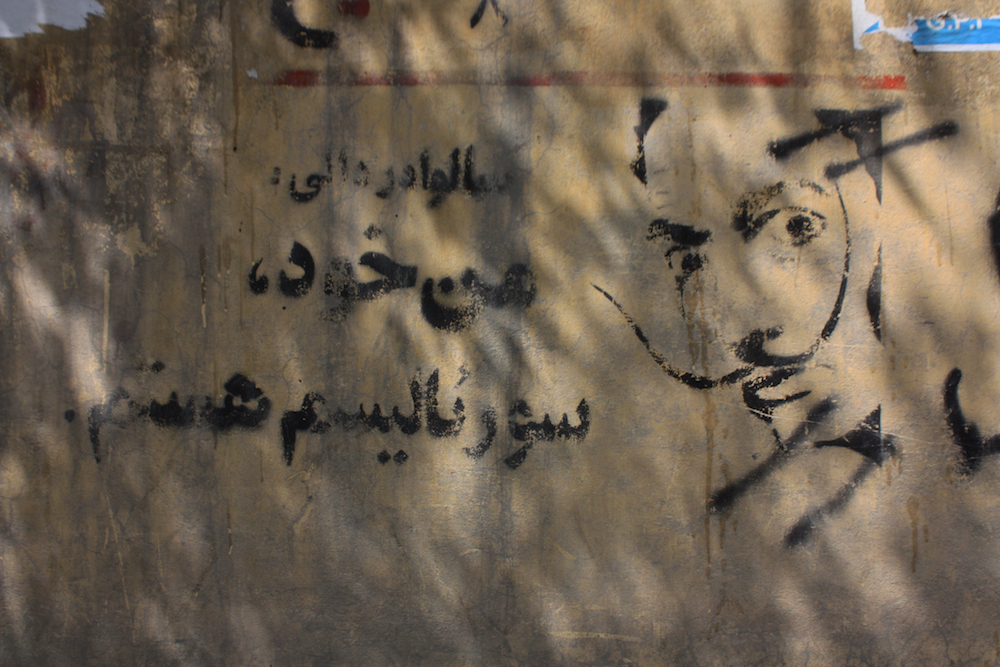

About your project on Kabul’s graffiti: «These new artists seek to create art that draws attention to, asks questions, comments and, more importantly, creates a dialogue around their work in the context of local and international issues. »: How do you believe that graffiti can serve this purpose? Do you see it as a mini-revolution in a city like Kabul?

Graffiti has always been a revolutionary medium, not only in its ability to break the usual boundaries of museums and galleries imprisoning art, but also creating an open form that rejects the traditional meaning of who can be an artist or what is art. Graffiti artists in Kabul, mostly in disguise because of the imminent dangers, not only bridge a dialogue between local and international issues and history through their works but also have developed a new way of expressing dissent toward traditions and politics. They take to walls to protest local leaders and traditions, or stamp people’s struggles in a community that freedom of expression still experiences boundaries and lives in the confines of a dangerous line that can’t be crossed through other mediums. It was the revolutionary smell of the walls as a medium, but also the messages carried through them, that captured my attention, and I think it possesses the potential to be an open platform for sharing and protesting that can’t be rivaled by other mediums.

Do you have a specific project in mind that you wish to carry out?

I am currently working on creating more works of my own and expanding my understanding of where I want to go with my practice. Besides that, I would like to find a venue to showcase 08.25.17, I believe it could have a far more powerful message and impact while witnessed in a physical space than its merely virtual presence at the moment.

Lastly, I have a long-term project focused on documenting and writing about the modern art movement in Kabul. I have been working on this project for several months now, but there is a still a lot more to be learned.

To know more about Muheb’s project : click here and/or here

And about his universe, click here

0 comments